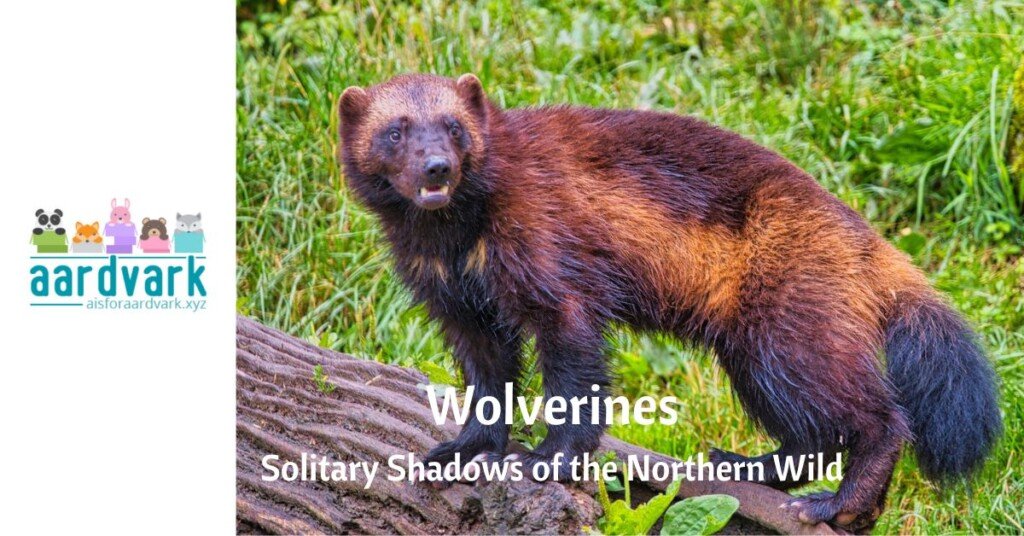

The wolverine (Gulo gulo) is a creature of extremes—fiercely independent, ruggedly built, and engineered for survival in some of the harshest environments on Earth. Although about the size of a medium dog, it commands a reputation far larger than its physical presence. Known for its strength, stamina, and near-mythical toughness, the wolverine thrives in the cold, remote reaches of the Northern Hemisphere.

Elusive by nature and solitary by habit, the wolverine has long fascinated biologists, Indigenous storytellers, and popular culture. While sightings are rare, the animal’s impact on ecosystems and imagination is anything but small. It is a survivor, a scavenger, and an emblem of the wilderness itself.

Taxonomy and Classification

Belonging to the mustelid family, the wolverine is related to weasels, otters, and ferrets. Its scientific name, Gulo gulo, translates from Latin to “glutton,” a reference to its voracious feeding habits. While it may seem fitting, the name doesn’t capture the nuance of a creature that must make the most of every meal in a landscape where food is unpredictable and scarce.

Though often mistaken for a small bear or wolf, the wolverine is neither. It is the largest terrestrial member of its family and has evolved to excel in environments where few other predators dare to roam. Popular media, particularly the Marvel superhero Wolverine, has helped introduce the name to millions, but the real animal is every bit as fierce and resilient as its fictional counterpart.

Physical Characteristics

Compact and muscular, wolverines are built to endure. Males typically weigh 10 to 18 kg (22 to 40 lbs), with females weighing slightly less at 7 to 12 kg (15 to 26 lbs). Their dense, water-repellent fur is dark brown with pale stripes that help them blend into snowy surroundings. Strong limbs, powerful jaws, and wide, fur-covered paws allow them to travel efficiently over deep snow and tear through frozen meat and bone.

A wolverine’s most defining feature may be its paws, which act like natural snowshoes. These adaptations, combined with a powerful neck and shoulders, give them the tools to not just survive but dominate their rugged environment.

Behavior and Temperament

Wolverines are solitary and highly territorial, covering immense areas—sometimes over 500 square kilometers—in search of food. While they are primarily scavengers, their boldness is legendary. They’ve been observed driving off much larger predators like wolves or bears to claim a carcass, not out of aggression but survival instinct.

These animals are also tireless travelers, capable of covering over 30 kilometers (20 miles) in a single day. In winter, they rely more heavily on scavenging, while summer offers opportunities to hunt small mammals, birds, and even vulnerable young ungulates. Wolverines cache surplus food, using the cold as a natural refrigerator and marking their stores with scent to deter thieves.

Habitat and Range

Wolverines are native to the boreal forests, tundra, and alpine regions of the Northern Hemisphere. They are most commonly found in Canada, Alaska, Scandinavia, and Russia. In the lower 48 United States, small populations persist in the northern Rockies, though they are increasingly threatened by habitat fragmentation.

These animals require large tracts of undisturbed land and are especially dependent on persistent snow cover for breeding. Females den in deep snowdrifts, where the insulation and concealment are critical for raising young. Climate change poses a significant threat by reducing these snowpacks and fragmenting the already limited suitable habitat.

Diet and Hunting Strategy

Wolverines are opportunistic feeders with a strong preference for meat. Their diet includes carrion from large mammals, small rodents, birds, and eggs. When food is abundant, they store it for later. Their ability to crush frozen bones and tear into hardened carcasses sets them apart from many other carnivores.

Although they aren’t fast enough to chase down large prey, wolverines occasionally kill weakened or trapped animals. Their sense of smell is so acute that they can detect prey hidden under several feet of snow. It’s not greed that drives them, but a survival strategy finely tuned to the lean and unpredictable rhythm of their environment.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

Wolverines breed in summer, but thanks to delayed implantation, embryos don’t attach until late fall. This ensures that kits are born in late winter when deep snow provides the safest den conditions. Females give birth to 1 to 3 kits in a snow cave, where the young remain hidden for the first couple of months.

By spring, kits begin to venture out, learning to forage and travel with their mother. They usually disperse by autumn to find their own territory. Wolverines reach sexual maturity around 2 to 3 years of age, and their lifespan in the wild ranges from 7 to 12 years.

Because females reproduce slowly and intermittently, population growth is limited. Combined with high juvenile mortality, this makes wolverine populations particularly sensitive to environmental change.

Cultural Significance and Mythology

Wolverines feature prominently in Indigenous stories throughout Alaska, Canada, and Siberia, often portrayed as clever, mischievous, and tenacious. In these tales, they serve as both tricksters and survivalists, reflecting the wolverine’s real-world adaptability.

In European folklore, the animal’s musky odor and secretive lifestyle earned it a reputation as something wild and unclean, yet impressive. In modern culture, Marvel’s Wolverine has redefined the animal’s image as a symbol of grit and unbreakable will, albeit with creative liberties.

Wolverines also serve as mascots for sports teams and military units, often representing toughness, courage, and endurance.

Conservation Status and Threats

Globally, wolverines are listed as Least Concern, but regional populations tell a different story. In the contiguous U.S., they are proposed for listing as threatened due to climate-related habitat loss. Without adequate snow cover for denning, reproduction declines. In Scandinavia and parts of Russia, legal hunting and trapping further stress populations.

Habitat fragmentation from roads, logging, and recreation pushes these animals into ever smaller ranges. Because they travel so far and reproduce so slowly, even small disruptions can have outsized effects. Conservation efforts focus on protecting wilderness areas, maintaining snowpack, and minimizing human encroachment.

Conclusion

The wolverine stands as a symbol of endurance and the raw power of nature. Small but mighty, elusive yet impactful, it is one of the last true icons of the wilderness. Its future depends not just on its own legendary toughness, but on our ability to protect the cold, wild places it needs to survive. As climate shifts and human footprints expand, preserving the shadowy, snowbound world of the wolverine is more important than ever.

By understanding and respecting this incredible creature, we preserve more than a species—we preserve a spirit of the untamed North.